An olive’s journey is governed by three tightly sequenced phenological steps; in each one the fruit is building a different asset: first volume, then structure, finally oil.

We are now in Phase 2, stone hardening. A pivotal moment for agronomic management when the aim is to produce top-grade extra-virgin olive oil.

Grounded in our own agronomic practice and backed by current scientific research, this post explores what’s happening today in the groves and explains the biological sequence that defines every great extra virgin olive oil.

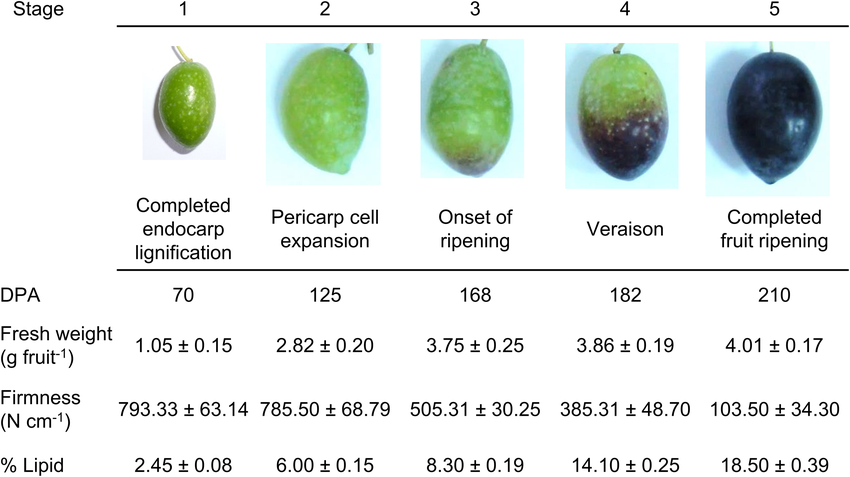

Phase 1: Rapid Cell Growth (Division & Expansion)

When? Late May to late June in Mediterranean groves.

After the flowers are pollinated and the tiny drupes set, the olive enters its first growth spurt. During the next five to six weeks the fruit’s job is simple: multiply cells and stretch them.

Up to 80 % of the cells that will one day hold oil are formed during this brief window.

As new cells appear, the existing ones fill with water and sugars, so the olive can double its diameter in barely a month. The future pit is still soft; its cells have begun to line up but have not yet turned woody.

What you won’t find yet?

Oil. Lipid bodies only start to appear once the pit has hardened, so oil content during Phase 1 is practically zero.

Why this phase matters

Think of each new cell as a “tank” that can later be filled with oil. If heat, water stress or nutrient shortages limit cell production now, the fruit will never be able to compensate later, no matter how favourable the conditions become.

Field pointers

- 10 days after fruit set: olives look like tiny green beads, still translucent.

- ≈30 days after fruit set: diameter reaches ~1 cm; growth curve begins to level off.When growers notice the pit resisting a gentle squeeze, Phase 1 is closing and Phase 2 is about to start.

In short, Phase 1 is all about building capacity. The tree lays down the cellular architecture that will later hold the oil, flavours and antioxidants we value in extra-virgin olive oil.

Phase 2: Stone Hardening (Endocarp Lignification)

When? Early July – early August, depending on cultivar and climate.

After the first growth spurt, the olive pauses to build its “armour.” During Phase 2 the soft inner layer of the fruit (endocarp) deposits lignin and gradually turns into the rigid pit that will protect the seed.

What happens inside the fruit?

- Lignin build-up: Cells of the endocarp stop dividing and start filling their walls with lignin: a tough, woody polymer. This sclerification transforms a pliable tissue into the hard stone familiar to anyone who has cracked an olive pit.

- Growth slowdown: As resources shift to lignification, the mesocarp (pulp) temporarily stops expanding. Diameter curves flatten and fresh-weight gain almost stalls for three to four weeks.

- Physiological pivot: Once lignification is complete, biochemical signals tell the fruit to begin synthesising oil in earnest; lipogenic enzymes ramp up and will dominate Phase 3.

Why this phase matters

The length and completion of pit hardening set the countdown to oil accumulation. In most Mediterranean cultivars, the pit finishes hardening about 80–90 days after full bloom: often in mid-July for early varieties (Arbequina) and late July/early August (Lecciana/Koroneiki) for later ones.

Because the seed is now shielded, the fruit becomes more tolerant of short water deficits: many growers therefore reduce irrigation briefly to curb canopy growth without harming future oil yield.

Field clues that Phase 2 is under way

- Fruit growth rate plateaus on weekly diameter readings.

- A gentle squeeze with the fingers reveals a firm pit that no longer dents.

- The skin remains bright green; external colour change will not appear until mid-Phase 3.

Phase 2 is all about structure: the olive forges its protective shell and flips the metabolic switch that will soon stock each mesocarp cell with oil.

Phase 3: Maturation and Oil Build-up (Lipogenesis)

When? Early August to late October, with cultivar and altitude causing small shifts.

During Phase 3 the olive resumes a modest increase in diameter, but the real change is in weight and oil content. Mesocarp cells that were merely watery “balloons” in Phase I now fill with triacylglycerols as enzymes channel previously stored sugars into lipid biosynthesis.

The most intense oil-accumulation period starts soon after the pit is fully lignified and continues for six to eight weeks, pushing the oil-to-fresh-weight ratio steadily upward until mid-October.

While oil droplets expand inside each pulp cell, the fruit also generates phenolic and aromatic compounds: oleuropein derivatives, flavonoids and a suite of volatile precursors.

These molecules are responsible for the bitterness, pungency, colour and antioxidant capacity that distinguish high-quality extra-virgin olive oil. Their concentrations rise together with oil, peaking earlier in the season and gradually declining as ripening advances.

During Phase 3 the fruit’s chemistry changes day by day, so the specific week we harvest determines both the oil’s flavour style and its commercial positioning.

Early harvest while the fruit is still green captures the peak of phenolic synthesis. The resulting oils deliver vivid grassy aromas, firm bitterness and a clean peppery lift.

Their high polyphenol load is prized in fine-dining kitchens, where a few drops can sharpen dishes without masking prime ingredients and where the antioxidant credentials add nutritional appeal. The trade-off is yield: the olives have not yet finished filling with lipids, so fewer litres are extracted per tonne.

Late harvest when the skin shifts toward purple lets triacylglycerol deposition continue for a couple more weeks.

Oil-to-fresh-weight ratio rises, the profile softens into a round, fruit-forward palate, and extraction becomes more efficient. Phenolic concentration and oxidative stability, however, begin to taper, making these oils better suited to recipes that prefer gentler notes.

In short, Phase 3 offers a sliding scale: early harvest for intensity, gastronomic prestige and maximum polyphenols; late harvest for volume, milder flavour and broader consumer appeal.

In conclusion

Phase 1 builds the olive’s cell “warehouses,” Phase 2 hardens the stone and flips the metabolic switch, and Phase 3 fills each mesocarp cell with oil and the phenolic compounds that determine flavour, colour and shelf life.

Reading these stages correctly allows us to harvest at the precise moment when chemistry, aroma and yield are perfectly aligned, ensuring dependable extra-virgin quality year after year.

Get in touch

If you have any questions or would like further details, please contact us and we will be happy to answer your questions.

Sources:

- Camarero, M. C., et al. (2023). Characterization of transcriptome dynamics during early fruit development in olive (Olea europaea L.). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(2), 961.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24020961 - Elsayed, S. M., et al. (2013). Growth curve of fruit development stages of three olive cultivars. Middle East Journal of Agriculture Research, 2, 25–30.

https://www.curresweb.com/mejas/mejas/2013/25-30.pdf - Rosati, A., et al. (2023). From flower to fruit: Fruit growth and development in olive (Olea europaea L.)—a review. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1276178.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1276178 - Gucci, R., et al. (2009). Water deficit‑induced changes in mesocarp cellular processes and the relationship between mesocarp and endocarp during olive fruit development. Tree Physiology, 29(12), 1575–1585.

https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpp086 - Sánchez‑Piñero, M., et al. (2022). Endocarp development study in full irrigated olive orchards and impact on fruit features at harvest. Plants, 11(24), 3541.

https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11243541 - Rapoport, H. F., & Pérez‑López, D. (2013). Fruit pit hardening: Physical measurement during olive fruit growth. Annals of Applied Biology, 163(1), 45–51.

https://doi.org/10.1111/aab.12046 - Sánchez‑Piñero, M., et al. (2024). Assessment of water stress impact on olive trees using an accurate determination of the endocarp development. Irrigation Science.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00271-024-00914-w - Skodra, C., et al. (2021). Olive fruit development and ripening: Break on through to the “-omics” side. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(11), 5806.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115806

Català

Català